Tate has a violent past that underpins his misogynistic messaging. In 2016, he was removed from the TV show Big Brother after a video seemed to show him attacking a woman with a belt. Last December, Tate was arrested in Romania, along with his brother, for allegedly exploiting women for his webcam business. They have been charged with rape, human trafficking, and forming an organised crime group [1].

Schools, teachers, and parents are now particularly concerned about the impact of children’s unregulated access to this kind of content online. Research reveals that 54% of children aged 6-15 have heard of Andrew Tate, rising to 84% of boys aged 13-15 years, and of those boys, 23% have a positive opinion of Tate [2]. Young children and adolescents are particularly susceptible to absorbing extremist content, and reports from schools reveal that the rise of Andrew Tate has led to an increase in misogyny amongst young boys in school and created a negative and unsafe environment for girls.

The issue is not just that children are able to access this content, it is that it is starting to shape the views and actions of young people, and young boys in particular.

Reports coming out of schools from teachers reveal that some pupils are using phrases associated with Tate and his ideas about masculinity. For example, “What colour is your Bugatti?” (a way of bragging about status) and “Make me a sandwich”, aimed at girls as a way to belittle them. Reports also detail a spike in controlling and harmful behaviours that mimic and express support for Tate [3].

“One boy was seen pinning his girlfriend to the wall by her shoulder; another was seen trying to confiscate his girlfriend’s phone.” [3]

A headteacher from a boy's school in Surrey said he has seen Tate’s influence spread through the school, “it’s got to a point, probably due to the arrests, that he is mainstream. In terms of student knowledge, it’s a common discussion point.” [3]

These accounts from teachers are supported by frontline charities. The founder of Bold Voices, a charity that empowers young people to tackle gender-based violence through workshops in schools, Natasha Eeles, says, “We can’t go into a school without hearing his name in every workshop.” Similar organisations such as Bold Voices, Everyone’s Invited, and Men At Work also report a huge increase in the number of schools asking them for support, specifically on Tate [3].

Now, secondary school teachers in England reportedly feel they didn’t pick up on Tate’s influence quickly enough.

Headteachers who have reached out for support have been told by the Department for Education (DfE) not to discuss Andrew Tate’s views with their students and have not been offered any training or resources. The DfE believes “this is merely another example of a social media trend, which will go away as others have,” and “heads have been told talking about him promotes him.” [4]

Many feel that this is not acceptable. Diversify, a charity that promotes social inclusion and delivers workshops on a range of topics, regularly gets calls asking for help dealing with sexual harassment and misogyny. Their co-founder Sara Cunningham said: “By not discussing this, we are leaving young people vulnerable to these vile, insidious ideas, unable to recognise them as being extreme and sharing them further." [4]

The charity talked to students in a primary school after an incident where a group of 9-year-old boys locked a girl in a cupboard and threatened to “fuck her in the throat” and made her watch porn. During the workshop, several boys spoke about Tate and didn’t see any problems with his views. The school was advised to report the incident to their local authority child safeguarding team but received no response. They were also asked by a secondary school to talk to pupils after a male student sent a girl a number of threatening and explicit sexual messages, once while standing outside her house. During the workshop, the student said “You shouldn’t take no for an answer [from a girl] as that shows weakness”, referencing Tate [4].

The problem is that many teachers do not feel well-equipped to have these conversations. Half of RSE teachers don’t feel confident having difficult conversations with their students because they are scared of getting it wrong due to the lack of support on how to address these issues [5].

It’s becoming clear that this is not an issue that will simply go away. According to research from Feminista, 66% of female secondary students and 37% of males have experienced or witnessed sexist language being used at school. 64% of teachers hear it weekly. Students are not only using misogynistic language in school; 37% of female secondary students have been sexually harassed at school, and 32% of teachers have witnessed sexual harassment weekly [6].

Men At Work, an organisation that offers advice on how to build constructive dialogues with boys and young men, has been asked for support by various schools. During one of their training sessions, teachers said, “We see misogyny every day in my school, with everything from boys ignoring instructions in corridors from female staff to serious sexual assaults...We need to do something.” [3]

Many children and young people spend a large amount of time online and increasingly have access to misogynistic content on TikTok, violent pornography, or sub-communities discussing violent views about women on platforms such as Reddit. Children are exposed to this kind of content from a young age. Ofcom found that 53% of children aged between 3 and 17 use TikTok regularly, despite the app being intended for users aged 13 and older [7].

An investigation into TikTok revealed that the platform promotes misogynistic content despite claiming to ban it. Videos of Andrew Tate, which have been watched over 11.6 billion times, are being pushed by the algorithm onto the For You pages of impressionable young people [8]. Videos of Tate also get shared on other social media platforms regularly used by young people, such as X (Twitter) and Instagram.

However, social media platforms are used widely by people from all age brackets, so why are young boys more likely to be influenced by this kind of content?

To gain a better understanding of why young boys are more vulnerable, we can lean on existing understandings of extremist ideology and the radicalisation of young boys into extremist groups. Founder of Men At Work, Michael Conroy believes that algorithms “make it possible for someone like Tate to be hugely well known to 14-18 year old boys.” Conroy argues that young men are being ‘groomed’ in a similar way to terrorist groups or gangs that target a similar age group. A teacher in London said, “It’s the most vulnerable and socially awkward boys that are drawn in and given a sense of belonging to something that is very dangerous.” [9]

Counter-extremism workers in the UK have also highlighted the rise in Andrew Tate-related cases and the risk of more young men being radicalised to misogynistic extremism. In recent years, the number of young men being referred to the government’s Prevent scheme over the misogynistic incel (involuntarily celibate) ideology, has increased significantly. Of these referrals, 36% came from educational settings from teachers concerned about male students [10]. However, Dr Tim Squirrell, of the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD), highlights that misogynist extremism relating to Tate is not currently recognised under the Prevent scheme and is only considered for support if accompanied by a recognised ideology, such as incel ideology. This is a key opportunity for policymakers and counter-extremism workers to formally recognise the risks of harmful misogynistic ideology [11].

Many young boys are also attracted to the image of masculinity that Tate promotes, especially if they don’t have an alternative idea of what masculinity is. A key aspect of Tate’s influence is his advice, which teaches his male followers to seek a luxurious lifestyle and dominate others, particularly women, in order to become an ‘alpha’ male. Jessica Ringrose, a professor at University College London said, “It’s not surprising that these kinds of norms are continuing to filter through when they’re being championed by somebody like Tate, who embodies these kind of superdominant, aggressive – ‘Here’s my Bugatti and my 30 cars and my knife collection’ – tough, virile masculinities." [3]

Family dynamics also play an important role in the development of a child’s values and beliefs about gender norms. Fathers and male role models in particular can play a role in either dismantling or reinforcing these kinds of beliefs. A secondary school teacher details that, after a young boy was disciplined for misogynistic language, his father responded that it was just “banter” and that girls “love it" [4]. Fathers and male role models, along with other influences like schools, might not realise how important their role is in giving children, particularly boys, a counter-narrative about masculinity.

Similarly, the quality of sex education that pupils receive can be an important risk factor in boys’ vulnerability to misogynistic content. The absence of topics such as consent, misogyny, and violence against women in the UK’s current sex education curriculum has drawn criticism. As a result, children are not being provided with the knowledge necessary for engaging in healthy sex and relationships. Instead, they are being taught harmful behaviours through media like online pornography and misogynistic content creators like Andrew Tate. In the government’s review of sexual abuse in schools and colleges, they found that pupils were largely negative about the sex education they had received in school. As there are so many gaps in the curriculum, they felt they had to use social media or their peers to educate each other, which made some feel resentful. “It shouldn’t be our responsibility to educate boys.” [12]

It is easy to dismiss misogynistic comments as ‘banter’, or minimise the impact that they can have, but it is important to recognise how narratives can escalate and feed into more harmful and aggressive behaviour.

A government report revealed that 92% of girls said sexist name-calling happens a lot or sometimes to them or their peers [12], and almost a third of girls don’t feel safe from sexual harassment in school [13]. Ofsted received 291 complaints in an 18-month period about peer-on-peer sexual harassment or violence [12].

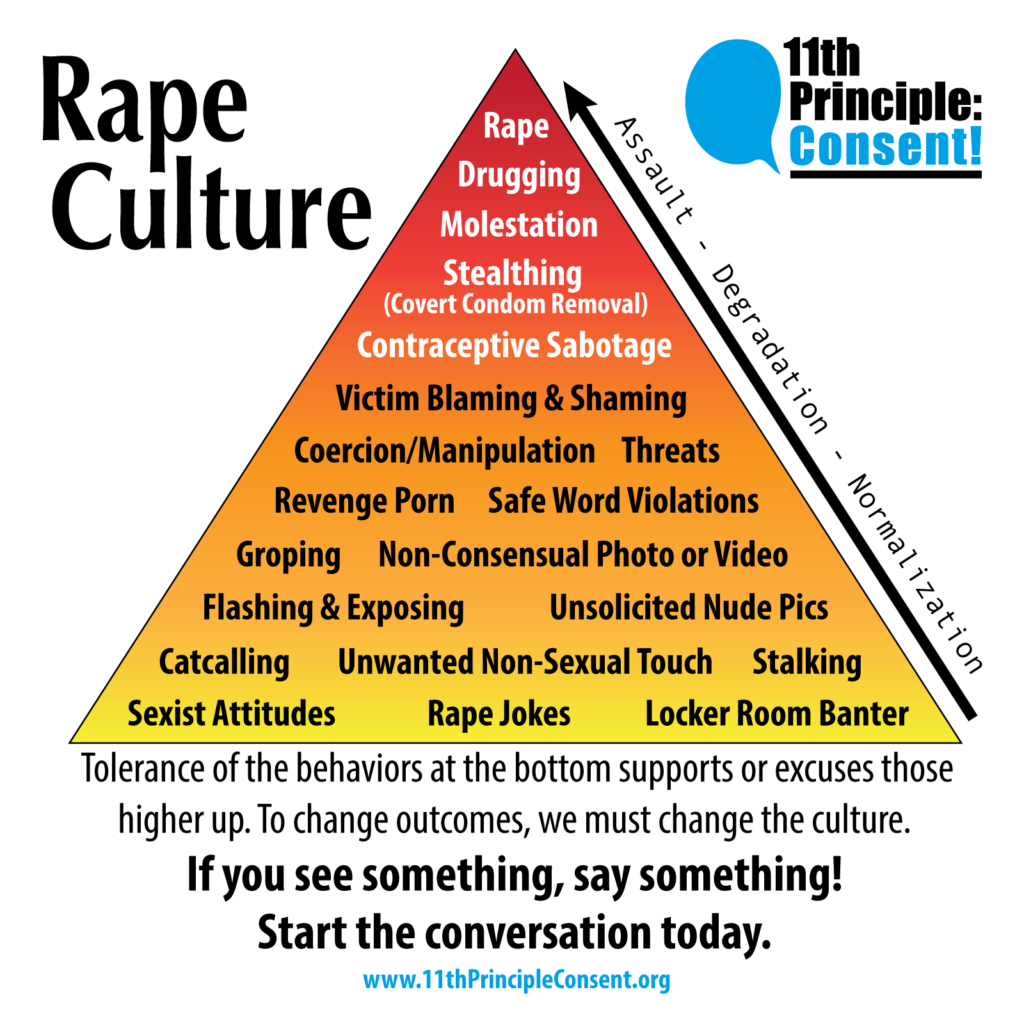

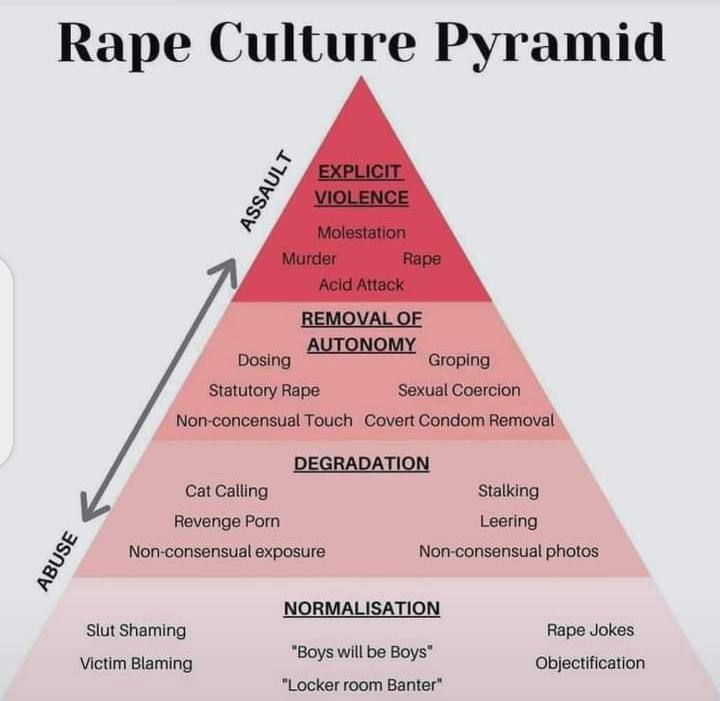

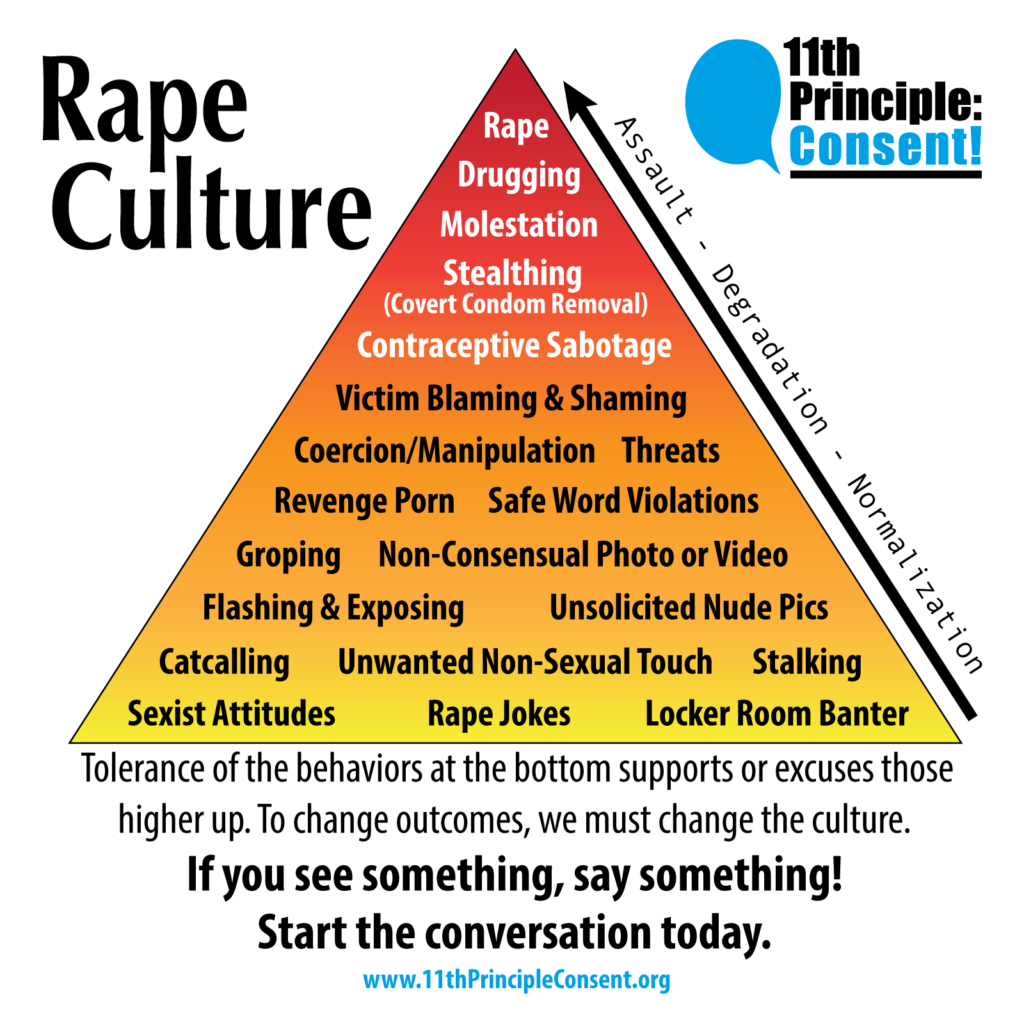

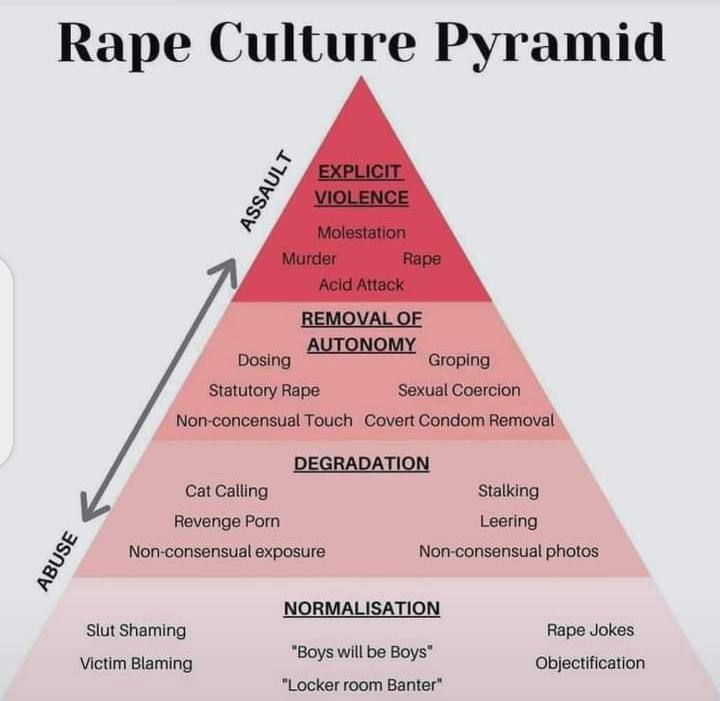

To illustrate this connection, we can use the ‘pyramid of violence’ or ‘rape culture pyramid’. The pyramid depicts how seemingly minor things that have become normalised, such as sexist banter and cat-calling, reinforce and excuse serious offences like rape and murder. These diagrams help to highlight how the full spectrum of misogynistic language and behaviour is underpinned by the same belief and can easily escalate. Tate’s language ranges from reinforcing gender stereotypes, saying that women belong to men, to openly violent language, such as if a woman accused him of cheating, he said he would “bang out the machete, boom in her face and grip her by the neck.” He also said part of the reason he moved to Romania was because it would be easier to avoid being charged with rape- “I'm not a rapist, but I like the idea of just being able to do what I want. I like being free.” [1].

When young boys begin to spout misogynistic abuse, it is built on the same foundations and beliefs towards women as more serious forms of violence, including rape and femicide, and therefore needs to be taken seriously.

(Top: 11th Principle Content, available here ; Bottom: Imtiaz Mahmood @ImtiazMadmood on X, available here)

Everyone’s Invited, a website created by Soma Sara for survivors to anonymously share their experiences of rape culture, has revealed the extent of sexual violence and misogyny in schools. Since these testimonies have come out there have been a number of high-profile murders of women, such as Sarah Everard, and an increase in the number of young men being referred to the Prevent scheme as a result of the incel ideology [3]. This shows how misogyny is deep-rooted in society, and negative influences like Tate just intensify it and are part of the bigger issue.

“It’s not about Andrew Tate; it’s about misogyny. These issues have been there forever” (Men At Work founder, Michael Conroy) he is worried about the amount of pornography children are exposed to; “porn is a huge accelerant to this.” [3]

64% of 13-21 year olds have seen pornography online, with 10% first exposed at age 9 and the average age of first exposure being 13. By 18 years old, 79% were exposed to violent porn [14].

Exposure to violent pornography can have harmful effects on young people. Research shows that almost 50% of 16 to 21-year-olds assume girls “expect” or “enjoy” sex which involves physical aggression, such as choking. Young people have expressed worries about how violent pornography affects an individual's ability to distinguish between harmful and pleasurable experiences during sex [15].

It is significantly more likely that young people will see a woman experiencing violence in pornography than a man. This behaviour is then reflected in real-life sexual encounters; 47% of those aged 18-21 have experienced a violent sex act, with girls being a lot more likely to experience this. This could be because those who regularly watch porn are more likely to engage in physically aggressive sex acts, and in the 2 weeks before the study, 21% of males aged 16-21 had watched porn at least once a day, compared to only 7% of girls [15].

Consuming harmful content, like violent pornography, builds a belief in young people that then influences how they act in day-to-day life. Their behaviour can then escalate and become more violent, as the pyramid conveys, which feeds into a wider epidemic of violence against women. For example, Rape Crisis states that those who inflict harm on women during sex might then move on to violent sexual crimes like rape. 1 in 4 women have been raped or sexually assaulted as an adult [16].

As boys grow older and start to enter romantic and intimate relationships, more factors could lead to things like misogynistic jokes escalating to violence. Poor sex education, along with consuming harmful online content, means young boys lack the knowledge on how to navigate these kinds of relationships. Tate makes young boys believe it is okay to treat a woman however they like because they are a man's property, and examples of violent behaviour towards girls in schools support this. As these boys get older, they may be in more positions of power, which allows for more opportunities for this kind of behaviour to materialise into physical harm against women. For example, 1 in 4 women experience domestic abuse from their male partner as adults [17]. This could then escalate further to sexual abuse and ultimately murder if this behaviour isn’t challenged during school.

Misogynistic influencers are promoting violence against women and girls, and this is having a worrying impact on boys’ attitudes and behaviour. “Schools and colleges are often left to deal with the aftermath of this. Addressing this issue in schools has never been more urgent.” [13]

Guidance from governments

More than half of teachers in the UK have never been given training on how to recognise and deal with misogyny in their school [6].

A whole-school approach is needed to create a culture where sexual harassment is recognised and addressed. Schools need to create an environment in which staff model respectful and appropriate behaviour for their students. A comprehensive RSHE curriculum is needed, as well as punishments and interventions to tackle poor behaviour, training for staff, and listening to pupil voice [12].

Improving sex education

The children’s commissioner says sex education should address pornography more effectively [15]. Young people should be taught that sex is supposed to be pleasurable, not violent or painful, like many learn from being exposed to violent pornography at a young age.

Several organisations create and run workshops for both students and teachers; Beyond Equality, School of Sexuality Education, Split Banana, Everyone’s Invited, Hope Not Hate, and Bold Voices are some examples. They all work with pupils on gender equality, gender-based violence, and misogyny, and some offer workshops for teachers to support them in talking to their pupils about these topics. These organisations have been shown to reduce sexual harassment and sexual assault among young people [5]. Bold Voices founder, Natasha Eeles, states that “None of our talks or workshops focus exclusively on Tate, as we try to support young people, staff and parents to understand the roots of gender inequality and gender-based violence and see Tate as one small part of that wider issue." [3]

High-quality sex education is so important for ensuring young people have the skills and knowledge they need to navigate healthy relationships and sexual encounters, and the importance of consent should be a priority. It is recommended that schools have a spiral sex education curriculum, which involves building student’s knowledge over time [5]. A curriculum that challenges the behaviours and beliefs that contribute to sexual violence can lead to a safer school environment and society.

Building safe spaces for open, non-judgmental conversations to dismantle harmful beliefs without boys fearing they will get in trouble

It is recommended that the government provide clear guidance on how schools can prevent and respond to sexual violence and that initial teacher training include a compulsory component on how to tackle sexism [6].

It is important not to criticise boys and blame them for misogyny, as this will further alienate them and make them more vulnerable to the influence of people like Tate. The focus should be on how to behave and be respectful towards women [5].

It is important for parents and teachers to understand how to talk to their children about online influencers like Tate. Lucy Russell runs online webinars, for example, ‘understanding and addressing Andrew Tate in your school’ and ‘discussing online influencers with your child’. Her tips for talking to your child about online misogyny include doing your research so you know what is online, listening to your child, and bringing up linked topics in relaxed conversations rather than having ‘the talk’. Some other tips for talking to young people about misogynistic influencers, such as Tate include having safe spaces for discussions and not limiting conversations to Tate, but discussing wider issues as well [5].

Positive male role models

Young boys are internalising the belief that they should be ashamed if they feel vulnerable or insecure, this is because there is a lack of positive male role models on platforms like TikTok.

Elliott Rae is a speaker and author who talks about fatherhood, masculinity, and men’s mental health. He hosts workshops that aim to empower parents to navigate online misogyny with their children and talk to them about problematic influencers like Andrew Tate.

Parents should be aware of people like Elliot Rae so that they are aware of what their children are being exposed to online and give them the support they need to have important conversations with their children. In school, teachers should have discussions with their pupils about positive male role models.

References

[1] 'Who is Andrew Tate, the self-styled 'king of toxic masculinity', awaiting trial in Romania?', Sky News. Available at: https://news.sky.com/story/who-is-andrew-tate-the-self-styled-king-of-toxic-masculinity-arrested-in-romania-12776832

[2] One in six boys aged 6-15 have a positive view of Andrew Tate, YouGov. Available at: https://yougov.co.uk/society/articles/47419-one-in-six-boys-aged-6-15-have-a-positive-view-of-andrew-tate

[3] ‘We see misogyny every day’: how Andrew Tate’s twisted ideology infiltrated British schools', The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/feb/02/andrew-tate-twisted-ideology-infiltrated-british-schools

[4] 'Don’t talk to pupils about misogynist Andrew Tate, government urges teachers in England', The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2023/apr/29/talk-pupils-misogynist-andrew-tate-teachers-schools-england

[5] 'Misogyny – Does your school have an ‘Andrew Tate problem’?', TeachWire. Available at: https://www.teachwire.net/news/misogyny-school-andrew-tate-problem/

[6] 'What’s the problem?', UK Feminista. Available at: https://ukfeminista.org.uk/resources/whats-the-problem/

[7] 'Children and parents: media use and attitudes report 2022', Ofcom. Available at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/234609/childrens-media-use-and-attitudes-report-2022.pdf

[8] 'How TikTok bombards young men with misogynistic videos', The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/aug/06/revealed-how-tiktok-bombards-young-men-with-misogynistic-videos-andrew-tate

[9] '‘Vulnerable boys are drawn in’: schools fear spread of Andrew Tate’s misogyny', The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jan/07/andrew-tate-misogyny-schools-vulnerable-boys

[10] 'Large rise in men referred to Prevent over women-hating incel ideology', The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/jan/26/large-rise-in-men-referred-to-prevent-over-women-hating-incel-ideology

[11] 'Andrew Tate-style misogyny falls through the cracks of current UK counterextremism policy', Institute for Strategic Dialogue. Available at: https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-in-the-news/andrew-tate-style-misogyny-falls-through-the-cracks-of-current-uk-counterextremism-policy/

[12] 'Review of sexual abuse in schools and colleges', GOV UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-sexual-abuse-in-schools-and-colleges/review-of-sexual-abuse-in-schools-and-colleges

[13] 'SCHOOLS: IT’S ABOUT TIME THINGS CHANGED', End Violence Against Women. Available at: https://www.endviolenceagainstwomen.org.uk/campaign/abouttime/

[14] 'Children first see online pornography aged just 13', SecEd. Available at: https://www.sec-ed.co.uk/content/news/children-first-see-online-pornography-aged-just-13

[15] '‘A lot of it is actually just abuse’- Young people and pornography', Children's Commissioner. Available at: https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/resource/a-lot-of-it-is-actually-just-abuse-young-people-and-pornography/

[16] 'Rape and sexual assault statistics', Rape Crisis. Available at: https://rapecrisis.org.uk/get-informed/statistics-sexual-violence/

[17] 'Domestic Abuse Statistics UK', National Centre for Domestic Violence. Available at: https://www.ncdv.org.uk/domestic-abuse-statistics-uk/#:~:text=1%20in%205%20adults%20experience,1%20in%206%2D7%20men